Meeting the risen Jesus in the tomb

The story is told of the drunk man walking home on a very dark, very misty moonless night through a graveyard. As can be expected because this is a story, he falls into a deep open grave that had been dug for the next day. He tries to get out, but as he clawed at the sides soil fell on top of him. He begins to get scared. Unknown to him, at the other end of the grave there is another man, who has also fallen in and who has also tried unsuccessfully to get out. So as he once again tries desperately to jump and claw his way out, he hears a whispery hoarse voice coming from the other end of the grave through the thick swirling mist: ‘You'll never get out of here’.

But he did.

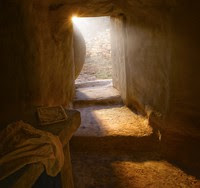

John had to go into the grave, into the tomb before he really saw and before he believed.

Mary comes and tells him that the stone has been removed. So

he runs with Peter to the tomb. He gets there first and he looks in – and he

sees the strips of linen.

He’s got all the evidence that he needs.

The stone rolled away, the grave clothes and the empty tomb.

The evidence of the linen cloths, the grave clothes, is particularly

significant. They tell us that the body could not have been stolen. Nobody

would steal a naked body without the grave clothes – there was no point; and because

the body had been anointed with spices it would have been almost impossible to

remove the linen strips.

But John doesn’t get it.

It is only when he goes into the tomb, after Peter, that we

are told, ‘he saw and he believed’.

He believed who Jesus was: the Son of God, the one who has come

from the heart of God to live among us and to give his life for us;

He believed Jesus’ words that whoever comes to him and receives

his word will know the truth, will be set free, and will have forgiveness and

eternal life.

I don’t know why he had to come into the tomb to get it.

Maybe he had to put himself where Jesus was.

Maybe as he crouched in the darkness where Jesus body had

been lain, he looked at the door and saw the light flooding in.

Maybe it was as he was in the silence of the tomb that he remembered

Jesus’ words.

He hadn’t understood them when Jesus first spoke them, but

now they began to make sense. ‘I will be arrested, crucified and on the third

day I will rise from the dead’.

But what we are told is that it is when John went into the

tomb that he saw and he believed.

It is significant that John speaks of himself not as John,

but as the disciple who Jesus loved. When he describes himself in that way he

is not only speaking of a fact – Jesus did love him – but he is also describing

himself as any disciple, any person who is following Jesus. In other words,

when a person who has chosen to follow Jesus reads about the disciple who Jesus

loved, we are not just reading about John. We are reading about ourselves. We

are the disciple, you are the disciple who Jesus loves.

Many of us are like John. We have heard rumours of a

resurrection. We have heard that the stone was rolled away, the linen strips were

left in the tomb and that the body of Jesus was not there. But we haven’t

really got it because we’re standing outside the empty tomb.

We’ve got to go in, if it is going to become real for us.

It means that we need to be willing to die to ourselves.

Often Easter is associated with baptism, and one of the meanings

behind baptism is that as the person goes down under the water, or as the water

is poured over them, so it is a picture of our death. We die to ourselves, to our

hopes, ambitions and fears, to our achievements and failures, to our good works

and our sins, to our likes and dislikes, our hatreds and resentments and

prejudices, our self-condemnation and our attempts at self-justification. And in

our baptism we died. We went into the tomb with Jesus. We were laid on the

sarcophagus with Jesus.

“Do you not know”, says Paul, “that all of us who were

baptised into Christ were baptised into his death? We were therefore buried

with him through baptism into death in order that, just as Christ was raised

from the dead, we too may live a new life” (Romans 6.3-4)

We hope that the resurrection is true. We hope that when we

die it is not the end. We hope that when those who we love die, it is not the

end. But it is a vague hope, and it is not the sort of hope that will make us

change the way that we are living now.

That is because we are standing outside the tomb and, even

if we have been baptised, we haven’t been willing to actually die to our self.

We haven’t knelt down and crawled into the tomb (do you notice how it says that

Mary had to bend down to look into the tomb). We haven’t yet been willing to

die to ourselves, so that we can come alive to Jesus.

One of the things that I find as a pastor is that it is often

when people discover that they are in the tomb that they begin to seek Jesus

and that they find the resurrected Jesus.

I hear the stories of people who have had near death

experiences, who have been brought back to life, who are convinced that Jesus

is alive and who have dedicated their lives to follow him.

I know of people who have been locked up in prison, and they

have met with the risen Jesus. They have discovered his forgiveness, his offer

of a new life, of hope and a future.

In one of my previous churches we ran a centre for asylum

seekers. We supported people who had fled from terrible ordeals, some of whom

had been quite significant in their former country; and now they were nobody and

nothing in a foreign land. All the things that they had depended on had been

stripped away from them. And we had the joy of seeing several of them meet with

the risen Jesus.

And when people come here from overseas, or when people from

here go overseas, and we find ourselves alone and helpless in a world that is

very different, and the things and the people which we have relied on are not

here, many of us begin to seek Jesus and meet with him.

There will, of course, be particular tombs, tombs in our

minds and memories, that we are not able to go into. Things that are just too

scary or too painful or too dark. That’s OK. But maybe there will come a time

when we need to be willing to crawl into those tombs, into those dark and

fearful places, on our knees, because we need to seek Jesus. We don’t have to

go on our own. We can go there with another person. But we know that we need to

revisit that place. But as we begin to crawl into the darkness we discover two

things. That Jesus was there, and that there is a way out: Jesus has conquered death

and is alive.

Gregory

of Nazianzus, one of the early theologians of the church, wrote a little poem:

Be

a Peter or a John;

Hasten,

hurry to the tomb,

Run

together,

Run

against one another,

Compete

in the noble race.

And

even if you are beaten in speed,

Win

the victory of showing who wants it more—

Not

just by looking into the tomb, but by going in.

(On Holy Easter, Oration 45.24)

One last thing.

Mary didn’t go into the tomb. But Mary doesn’t need to.

Because for Mary it was already dark. She comes in the morning when it was dark.

She had lost the person who gave her life direction and meaning. The Greek word

that is translated as weeping is actually ‘heaving’. Her heart was broken. She

might as well have been dead. She was already in the tomb.

But it was her grief and confusion that made her desperately

seek Jesus.

She runs to Peter and John and tells them, ‘we don’t know

where they have put him!’

She says to the angels, ‘I don’t know where they have put

him’

And she is so distraught that she cannot see or recognise Jesus

but thinks that he is the gardener.

And what is interesting is that although she thought that

she had utterly lost him, as she sought him, he had been there all the time.

And it is then that she hears the risen Jesus speak to

her. He calls her by her name.

Comments

Post a Comment