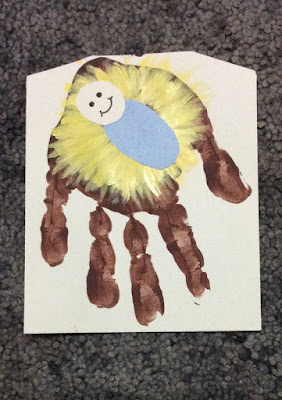

The hand of God in the manger. A Carol service talk for 2020

Christmas is a time of coming together

One of the things that I have missed this year have been handshakes.

Handshakes are a significant part of our social skills set, particularly for men, and particularly here. They are a sign of acceptance and approval. And to refuse the hand of another when it is offered to you, even if you are doing it in their best interests, is to feel that you are treating them like a leper, as if they had the plague (even though the reason you are doing it is because you are possibly the one with the plague!).

If you are shaking the hand of another, then you can turn your face from them, but you cannot turn your back on them. You are giving a little bit of yourself to the other. You become part of them for an instant.

At Christmas, God breaks through the barrier that separates us from heaven and offers his hand to us.

It is a pure clean uninfected hand reaching out to our filthy unclean infected hand

It is a sign of his love for us, his forgiveness offered to us, his acceptance of us.

And he offers us his hand knowing that when we take it, we will become part of him and he will become part of us.

The consequence of the virus that we have, the virus of sin and death, will pass to him.

And he offers us his hand, knowing that he will suffer the results of our deadly infection. And that happens when 33 years later, we nail his hands to a wooden crossbeam, and he dies on the cross.

In some of the earliest Christian imagery of the nativity, we see how the baby wrapped in swaddling clothes could also be the body of Jesus wrapped in the graveclothes and laid in the tomb.

But in coming among us as one of us, God offers his hand to us. He invites us to receive it, because in receiving it, we will become part of him – for as long as we want to hold onto him. He knows that if we receive it then his love and his life and his peace will pass to us.

It will be like a good infection that is passed to us. It will do its invisible work, giving us purpose, peace and hope and life.

As John writes, ‘To all who received him, he gave the right to become children of God’

Christmas begins with the bringing together of God and humanity in the baby in the manger

Christmas is also about the hope that one day all will be brought together

Our hope as Christians is that the child who came to bring peace between God and us, will also bring peace between people. He alone can remove the sin and fear which divides us.

The tragedy is that while we live in this world of sickness and sin, of fear and mistrust, and especially in the current crisis, there need to be physical barriers in place between peoples.

Much as I do not like it, I need to be in quarantine!

But when God offers us his hand, he knows that when we receive it, we will also become part of everyone else who receives him. Just as he has become part of us, so he will become part of them, and we will become part of them.

As the church we should, in some small way, begin to embody that. And I treasure the fact that at most of our services, the central act is a symbolic meal when – in normal times - we eat bread from one loaf and drink wine from one cup. And we can have people from about 30 different nations gathered here – coming not only to receive from his hand, but coming to receive that offered hand

So although this will be a very different Christmas, in which you may be separated from those who you love, I do pray that you will see the hand in the manger – the hand of God offering himself to us. And I pray that as you take that hand, you will again know the love that comes from God, the forgiveness, acceptance and peace that he offers, and that you will know the hope of Christmas

The hope that rests on the love of God

The hope that in Bethlehem God came from heaven and kissed the earth

The hope that one day there will be a world in which there will be no more sin or sickness and no more need for barriers or borders or walls.

And the hope that one day, when together with all who have welcomed and received the Lord Jesus, even those who we have loved and lost, heaven and earth will finally come together, and we will see Jesus face to face.

But this year for many it is a time of separation

We are now separated from you, and we are not alone. There are many who are having to quarantine or to self-isolate.

Many here have been separated from their families because of closed borders

And many this year have been separated from those they love by what seems to be the final barrier, by death.

But the message of Christmas includes the hope that those who are separated can be brought together.

It begins with the bringing together of God in heaven and human beings on earth.

We heard in our readings how, because of human sin, our rebellion against God, human beings were cast out of the garden of Eden, cut off from God.

And without God we are lost – we do not know why we are living, what to live for, or how we should live. Of course, most of the time we do not think about those sorts of questions. But when we do think about them, we realise that our only reference point is ourselves and that we are alone and without hope. And those we love will die and we will die.

But we also heard through the prophets that God created us and he loves us. He created us for far more than this. He created us that we might know him, that we might care for this creation as his co-rulers, that we might delight in him and in each other and in this universe that he has given us, that we might become and live as his sons and daughters, free of sin and sickness and death.

And so, at the first Christmas God reached out to us in forgiveness and in love.

We could not get to him – we had become too disorientated – but he came to us.

He broke the barrier of our rebellion and of our hard-heartedness and of our blindness to him

The child was born and the angels announced the birth to the shepherds. They sang, ‘Glory to God in the highest and on earth, peace, good will towards human beings with whom he is pleased’.

At Christmas, God, the Son of God, comes to us from heaven and is born for us in a stable

When I worked, many years ago, in a parish in inner London, there was a lady who lived in what can only be described as a shed. She was called Mary. She was in a dreadful state. Her face was filthy and all pocked and scarred, and she stank. The local kids called her smelly Mary, and they made her life hell.

One day Mary came to our church. She sat down in the back row, and nobody sat near her.

We came to the peace and I noticed that everyone, when they started to shake hands (do you remember the days when we could do that?) avoided her. But one lady, Annette went up to Mary. She didn’t shake Mary’s hands. Instead, she said, ‘Mary it is lovely to see you’. And then she kissed her.

At Christmas, God comes to filthy stinky pocked and scarred humanity, and he kisses us.

Many here have been separated from their families because of closed borders

And many this year have been separated from those they love by what seems to be the final barrier, by death.

But the message of Christmas includes the hope that those who are separated can be brought together.

It begins with the bringing together of God in heaven and human beings on earth.

We heard in our readings how, because of human sin, our rebellion against God, human beings were cast out of the garden of Eden, cut off from God.

And without God we are lost – we do not know why we are living, what to live for, or how we should live. Of course, most of the time we do not think about those sorts of questions. But when we do think about them, we realise that our only reference point is ourselves and that we are alone and without hope. And those we love will die and we will die.

But we also heard through the prophets that God created us and he loves us. He created us for far more than this. He created us that we might know him, that we might care for this creation as his co-rulers, that we might delight in him and in each other and in this universe that he has given us, that we might become and live as his sons and daughters, free of sin and sickness and death.

And so, at the first Christmas God reached out to us in forgiveness and in love.

We could not get to him – we had become too disorientated – but he came to us.

He broke the barrier of our rebellion and of our hard-heartedness and of our blindness to him

The child was born and the angels announced the birth to the shepherds. They sang, ‘Glory to God in the highest and on earth, peace, good will towards human beings with whom he is pleased’.

At Christmas, God, the Son of God, comes to us from heaven and is born for us in a stable

When I worked, many years ago, in a parish in inner London, there was a lady who lived in what can only be described as a shed. She was called Mary. She was in a dreadful state. Her face was filthy and all pocked and scarred, and she stank. The local kids called her smelly Mary, and they made her life hell.

One day Mary came to our church. She sat down in the back row, and nobody sat near her.

We came to the peace and I noticed that everyone, when they started to shake hands (do you remember the days when we could do that?) avoided her. But one lady, Annette went up to Mary. She didn’t shake Mary’s hands. Instead, she said, ‘Mary it is lovely to see you’. And then she kissed her.

At Christmas, God comes to filthy stinky pocked and scarred humanity, and he kisses us.

One of the things that I have missed this year have been handshakes.

Handshakes are a significant part of our social skills set, particularly for men, and particularly here. They are a sign of acceptance and approval. And to refuse the hand of another when it is offered to you, even if you are doing it in their best interests, is to feel that you are treating them like a leper, as if they had the plague (even though the reason you are doing it is because you are possibly the one with the plague!).

If you are shaking the hand of another, then you can turn your face from them, but you cannot turn your back on them. You are giving a little bit of yourself to the other. You become part of them for an instant.

At Christmas, God breaks through the barrier that separates us from heaven and offers his hand to us.

It is a pure clean uninfected hand reaching out to our filthy unclean infected hand

It is a sign of his love for us, his forgiveness offered to us, his acceptance of us.

And he offers us his hand knowing that when we take it, we will become part of him and he will become part of us.

The consequence of the virus that we have, the virus of sin and death, will pass to him.

And he offers us his hand, knowing that he will suffer the results of our deadly infection. And that happens when 33 years later, we nail his hands to a wooden crossbeam, and he dies on the cross.

In some of the earliest Christian imagery of the nativity, we see how the baby wrapped in swaddling clothes could also be the body of Jesus wrapped in the graveclothes and laid in the tomb.

But in coming among us as one of us, God offers his hand to us. He invites us to receive it, because in receiving it, we will become part of him – for as long as we want to hold onto him. He knows that if we receive it then his love and his life and his peace will pass to us.

It will be like a good infection that is passed to us. It will do its invisible work, giving us purpose, peace and hope and life.

As John writes, ‘To all who received him, he gave the right to become children of God’

Christmas begins with the bringing together of God and humanity in the baby in the manger

Christmas is also about the hope that one day all will be brought together

Our hope as Christians is that the child who came to bring peace between God and us, will also bring peace between people. He alone can remove the sin and fear which divides us.

The tragedy is that while we live in this world of sickness and sin, of fear and mistrust, and especially in the current crisis, there need to be physical barriers in place between peoples.

Much as I do not like it, I need to be in quarantine!

But when God offers us his hand, he knows that when we receive it, we will also become part of everyone else who receives him. Just as he has become part of us, so he will become part of them, and we will become part of them.

As the church we should, in some small way, begin to embody that. And I treasure the fact that at most of our services, the central act is a symbolic meal when – in normal times - we eat bread from one loaf and drink wine from one cup. And we can have people from about 30 different nations gathered here – coming not only to receive from his hand, but coming to receive that offered hand

So although this will be a very different Christmas, in which you may be separated from those who you love, I do pray that you will see the hand in the manger – the hand of God offering himself to us. And I pray that as you take that hand, you will again know the love that comes from God, the forgiveness, acceptance and peace that he offers, and that you will know the hope of Christmas

The hope that rests on the love of God

The hope that in Bethlehem God came from heaven and kissed the earth

The hope that one day there will be a world in which there will be no more sin or sickness and no more need for barriers or borders or walls.

And the hope that one day, when together with all who have welcomed and received the Lord Jesus, even those who we have loved and lost, heaven and earth will finally come together, and we will see Jesus face to face.

Comments

Post a Comment