Living the TRI-uNITY

Romans 8.12-17

This is at first sight, a strange passage for Trinity Sunday: it should really be a reading for Pentecost because it is about the Spirit – about being led by the Spirit.

This is at first sight, a strange passage for Trinity Sunday: it should really be a reading for Pentecost because it is about the Spirit – about being led by the Spirit.

But the Spirit cannot be separated from the Father or the

Son.

For a start, the Spirit here is described as ‘the Spirit’, as the ‘Spirit of God’ (v14), and as the ‘Spirit of Christ’ (v9).

And we are told that the Spirit is the Spirit of adoption

(v15):

If we are led by the Spirit, we are adopted into God’s

family.

We are not, in our human fallen state, children of God –

not children in that special way.

But when the Spirit of God, or the Spirit of Christ,

comes into our lives, when we receive the Spirit, we are born again – or ‘from

above’ – by the Spirit.

And we become adopted children in the family of God.

And as people who have the Spirit, that means that we

have all the privileges of being sons and daughters of God.

And now we’re beginning to speak about Trinity.

The Trinity is not a problem to be solved but a

relationship to be lived.

Western theology begins with the unity of God and then

tries to work out how One can be Three at the same time.

We turn it into a logical, mathematical problem and try

to solve it with Venn diagrams or three leafed clovers. And that is not particularly helpful.

Eastern theology – which is becoming more mainstream in

the West – begins where the bible begins with: the three persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. And it asks

how can they be one.

It begins with the TRI – and adds uNITY on.

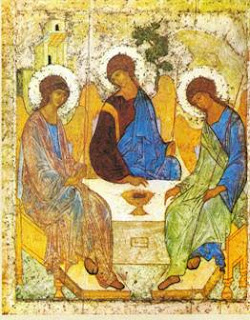

The most well know illustration of this is Rublev’s

utterly inspirational Trinity icon.

Popularised in Western literature by William Young in his

book ‘The Shack’; used by someone with conservative theology like Tim Keller, in a brilliant chapter in his book: The Reason for God, called the Dance of God; and used and I think a bit abused by someone like Richard Rohr, ‘The Divine Dance’.

The point here is that we are not trying to define what is

the nature, the essence that makes them one God, but we are looking at them as three

persons who are in relationship with each other. And we are looking at that

relationship.

So the Father is the source of life for the Son, and he

loves the Son, and delights in the Son. At Jesus' baptism and transfiguration,

the voice from heaven says, ‘This is my Son, my beloved in whom I delight’. And

he will give the Son all things.

We’re obviously talking about a reality here that is bigger

than language and our logic.

Because the Son is the Son of the Father, but there has

never been a time when he was not the Son.

And the Son is the heir of the Father, even though there

will never be a time when the Father is not.

But because the Father delights in the Son, he shares all that he has with the Son, and he seeks the

glory of the Son. He wants everybody to know – the whole of creation – how utterly

amazing and wonderful his Son is.

And the Son loves the Father. Although he is eternally

equal with the Father, when he becomes a human being he humbled himself and

became obedient to the Father – so obedient that he was even prepared to be

crucified. And the Son delights in the Father. Every word his Father speaks is

a joy to him. And because they are so united, what he speaks and what he does

is what the Father would speak and what the Father would do. You see, they have

the same Spirit.

And because the Son delights in the Father, he seeks

the glory of the Father. He wants everybody to know – the whole of creation –

how utterly amazing and wonderful the Father is.

It is like two lovers: delighting in each other,

declaring the praises of each other. And if we follow the human analogy it

could appear quite exclusive.

But it is not just two – but three. And we have already

spoken of the Spirit. He comes from the Father but is also in the Son. And he is sent to us by the Son. And the

Spirit loves the Father and the Spirit loves the Son, and the Spirit longs to draw people to the Son.

So what we have here (and again forgive me for well oversimplifying this) is a hug – three persons in close

communion – who have always been there and who will always be there, delighting

in each other, seeking the glory of the other.

And as we look at that hug, is

that three or is that one?

But this is also an open hug. Because, and I’m finally getting

back to our passage(!), the Spirit, who comes from the Father but is sent by

the Son of God (who is now in glory), comes to us and invites each one of us to

join the Son in the embrace of his Father.

And what that means is that if we are led by the Spirit, if

the Spirit of the Father and of Christ lives in us, we are now living here: in

this relationship.

And that has some pretty big consequences for us here and

now:

1. We will be able to begin to live like the eternal

Son of God, like Jesus.

‘So then brothers and sisters

we are debtors, not to the flesh, to live according to the flesh .. [but to

live according to the Spirit]’ (v12). It is not said but it is implied.

We will want to be obedient to

the Father.

We will want to read his word,

because these are the Father’s words.

We will want to come to Church

to meet with God’s people, to share in this communion.

And we will want to draw

others into this hug.

And because we are led by the Spirit, because the Spirit of Christ is in us, we are no longer to be controlled by slavery or fear.

'For you did not receive a spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received a spirit of adoption' (v15)

We watched Bizet's Carmen last week. The seargant is infatuated by Carmen, enslaved by his desire for her and his fear of losing her; but Carmen also is driven, enslaved by forces that are far greater than her: the desire to be loved and the fear of being trapped.

And we are enslaved by our desires and driven by our fears: lest our love is lost, our identity becomes meaningless, our freedom becomes imprisonment, our status becames shame and our comfort turns to pain.

But in place of that we have a new way of living: where we find identity and freedom in our relationship with the Father, Son and Spirit: we discover that this is who I was made to be.

And yes, because we are here –

in this hug – and because, together with the Son, we delight in the Father and

we long to see glory come to the Father (think of the prayer we pray: ‘Our Father

in heaven, hallowed be your name’), we will be prepared to suffer for his sake

(v17). And if we are not prepared to suffer for his sake, not prepared to put

ourselves out for him, then it does mean that we need to question whether we are

actually yet part of this hug.

2.

We have

intimacy with the Father.

With Jesus, we can call God, ‘Abba’, which means ‘Dear Father’ (v15).

With Jesus, we can call God, ‘Abba’, which means ‘Dear Father’ (v15).

There is so much that could be

said here!

But all that I will focus on here is to say that prayer is a discipline and a duty;

But all that I will focus on here is to say that prayer is a discipline and a duty;

it is something that we have to force ourselves to do – because the old

self-reliant, god-rebelling nature is pretty deep rooted in us – but prayer can

also be an utter delight and totally liberating.

It is about ‘saying our

prayers’, but it is also about relationship.

The Cure of Ars (whoever he was) tells the story of the old man who used to sit for hours in church. They asked him what he was doing. He said, ‘I’m saying my prayers’. And they said to him, ‘You must have a lot to say because you are there for so long’. And he replied, ‘No. Most of the time He looks at me and I look at Him’.

The Cure of Ars (whoever he was) tells the story of the old man who used to sit for hours in church. They asked him what he was doing. He said, ‘I’m saying my prayers’. And they said to him, ‘You must have a lot to say because you are there for so long’. And he replied, ‘No. Most of the time He looks at me and I look at Him’.

I do hope that you do put

aside time regularly, daily, to pray. That is a discipline and, I guess, is

part of the ‘suffering with him’. But I also pray that you have begun to

discover a little bit of the intimacy of being in the Trinity, and of the delight of simply being with the Son together with the Father.

3. We have an astonishing hope

‘… if children, then heirs, heirs

of God and joint heirs with Christ’ (v17)

All that belongs to the Father

– that is all things: everything in creation, every gift, everything that is a

blessing, every object and every person - he has given to his Son.

And as people who, through the

Spirit, share in this hug, all things belong to us.

They are part of us just as we

are part of them.

We’re responsible for them and

for each other, just as the manager of a company is responsible to his board and shareholders for the management of the company. The word that is often used is that we are

to be good stewards of creation.

So yes, all things belong to

us.

The hug of Father, Son and Spirit

is the eternal hug. It is bigger than death.

If you are part of this hug then - unless you are like Enoch and Elijah - of

course you will die physically, but you will never really die.

That is why we are told that

the meek will inherit the earth, that in the kingdom we will rule this creation

together with Christ.

My brothers and sisters, in

Christ, in the TRI-uNITY, we really do have a glorious calling, an intimate

relationship and a wonderful destiny.

Comments

Post a Comment