A Christmas day talk based on the life of St Nicholas

I’d like to tell you about someone quite obscure – although

I am certain that everybody here – apart from the very smallest - will have

heard of him!

He lived 1600 years ago, in an Greek town called Myra.

Today Myra is in modern day Turkey, and it is in ruins.

We don’t know that much about him.

He was a Christian born to a well-off family.

We know that he was really serious about his Christian

faith, and he was deeply committed to Jesus. When his parents died, he took

Jesus’ command to ‘sell everything and give to the poor and come follow me’ quite

literally. He gave away his wealth; he became a priest, and subsequently the

bishop of Myra.

Although nothing was written down, they told stories

about him: about his love for God, for God's word and his love for people; and about how God

did astonishing things through him.

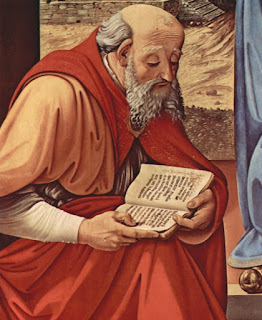

This is an icon of him. Around the edge

are scenes from his life. In the centre, he is shown wearing a bishop’s scarf.

His right hand is raised in prayer and blessing – he is praying God’s blessing

on his people. In his left hand, he holds a bible and a towel.

There are stories of how he prayed for people and they

got better; and, on one occasion, how three people were brought back from the

dead. There are stories of how, even after he had died, people had visions of

him, or they went to his tomb and were healed. I don’t know what to make of

that – although I do know this: that when a person commits themselves to Jesus

Christ, and when they live for him, put their trust in him and ask him to come

and live in them, astonishing things happen.

But this person is inseparably connected with Christmas

And there are two reasons:

One of the most well-known stories that is told about him

is of the time when he heard about a widow who had three daughters. They had no

money, and the only option if they were going to survive was for the girls to

sell themselves to traffickers. Nicholas, for that is the name of this Bishop

of Myra, walked past their window and threw in three bags of gold: sufficient

for each of the girls to have a dowry.

And since then Nicholas, who in time became St Nicholas

(in some places known as Santa Niklaus), has been associated with the giving of

gifts to children.

I don’t know where the sleigh or the reindeer have come

from – well, I do, Lapland! – but I do know that at the heart of it all was a

man who loved God and who loved people and who, as a result, gave secretly and gave

generously.

But there is a second reason that he is associated with

Christmas.

It is said that he travelled to Nicaea for the big

council of bishops, who were meeting because of a wrong teaching that was

spreading through the Church.

The wrong teaching was about who the baby in the manger

really was.

It began with a man called Arius, who said that Jesus was

not the eternal Son of God. He was instead a super mega angel, created by God.

The story goes that Nicholas got so angry with Arius at

the meeting, that he went up to him and smacked him round the face. That shows

a commendable zeal for the truth, although it is not behaviour that I would

encourage when you come to talk about your Christian faith.

But there is a connection.

What we believe

about the baby in the manger – about who he is – makes a big difference to how

we live.

If we look at him, as Arius did, as a super mega angel

sent from God to come to earth, then there is still a gap between us and God.

There is us, there is the angel, and there is God. But in between us and the

angel and the angel and God there is a huge gap.

And if you believe, with Arius, that God is up there and

we are down here, then the only way we can begin to get to know God, or to get

God on our side, is for us to climb the ladder to get to God. We need to be sufficiently

religious or good enough.

We listen to Jesus’ teaching; we look at him as an

example of how we should live

And we think that if we want God to like us and give us

what we want, then we need to become better people, more prayerful, more

loving, more giving.

There is the story told of the little boy who wanted a

bike for Christmas. His mother heard him praying: ‘Dear God, if you give me a

bike for Christmas, I’ll be good for a year’. His mother said to him, ‘It

doesn’t work like that. God doesn’t give us things because we are good, even

good for a year, because we can never be good enough’.

So on the second day, she heard him praying, ‘Dear God,

my mum says that being good for a year is not enough, so what if I was good for

a year and came to church every Sunday for a year? Would you please give me a

bike for Christmas?’

Again, his mum said to him, ‘It doesn’t work like that.

God doesn’t give us things because we go to church, because we would never be

religious enough’

The next day she noticed that a small statue of Mary had

gone missing from the lounge. She couldn’t find it anywhere. But when she went

into her son’s room she found a note pinned to his bedroom window: ‘God, if you

ever want to see your mother again …’

But if you believe with St Nicholas that the baby born in

the manger is the eternal Son of God, that he is Immanuel, which means ‘God is

with us’, then

·

We don’t need to cut a morality deal with God in

order to make him like us.

·

We don’t need to become religious enough in

order to make God like us.

We don't need to get to God because God has already come to earth. God has bridged the gap.

That is what the bible teaches. ‘The Word became flesh

and dwelt among us’

It is what Jesus teaches. ‘Philip’, he says, ‘whoever has

seen me has seen the Father’.

It is what Wesley celebrated when he wrote Hark the

Herald Angels sing, with the line ‘veiled in flesh the Godhead see’.

Jesus was the eternal Son of God. Everything he was

saying, doing and being on earth was what God was saying, doing and being in

heaven.

All we need to do is to receive this simple but stunning

fact: that the baby in the manger is the Son of God, that God came to us at

Christmas, that he is Immanuel ‘God with us’.

There is a precious verse in John’s gospel (John 1.12): ‘to all who

received him, who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of

God’.

Arius couldn’t get that. He said it wasn’t God but a

super-mega angel that God had sent

Our modern secular world can’t get it. They say it wasn’t

God but a baby who grew up to be someone very special.

But Nicholas did get it. He realised that we don’t need

to get to God because at Christmas God came to us.

St Nicholas was quite ordinary. He didn’t write anything.

He didn’t die a martyrs’ death. He even smacked someone across the face (and got into trouble for it). But, according to the stories, he lived a very

special life: he was prayerful, he was good and he was generous.

So when you see Santa Claus:

Thank him for his generosity. It is good to say thank you.

Thank him also for letting God show him that the baby in the manger was the eternal Son of God, Immanuel, God with us, and for his passion in showing us that we don't need to strive to get to God, because God has come to us.

All we need to do is to receive the love of God, to trust our lives into the hands of this God of love and allow that love of God to work in us, to transform us, so taht we reach out in works of love, power and deep generosity.

Comments

Post a Comment