A selected diary of a sabbatical 2

I have now been on sabbatical for 6 weeks. I'm loving it, although do miss the people in our churches greatly. It was very good to spend time with people again at the parish weekend, and also to see several at Matthew's ordination.

I have now been on sabbatical for 6 weeks. I'm loving it, although do miss the people in our churches greatly. It was very good to spend time with people again at the parish weekend, and also to see several at Matthew's ordination.However, I have to admit that waking up on a Sunday morning without the feeling of responsibility for several services is a real joy! It has also meant that we have been able to visit different churches. So it has been a delight to have worshipped at Rougham Baptist Church, the Cathedral, Holy Trinity Norwich and, a couple of weeks ago, while staying a few days with my mother in Nottingham, Cornerstone church. We've heard some great preaching: at Holy Trinity, Norwich, one of their readers, Diana Timms, gave a brilliant expository sermon on Elihu's speech in Job 33, and on how God speaks in and through suffering. I was particularly struck by two verses that she drew our attention to: Job 35:9-10, "People cry out under a load of oppression; they plead for relief from the arm of the powerful. But no one says, 'Where is God my maker, who gives songs in the night'." Even in the darkest moments of suffering, we are to look to God, who does give us those 'songs in the night', glimpses of his grace in the worst of moments. The following week, at Cornerstone Church, Peter Lewis gave an exceptional talk on science and faith: full of grace, wisdom and profound insight. If this is an issue which interests you, then it is a long talk, but I would recommend it.

I have to confess to some envy at Cornerstone: a congregation of 600 plus, with people of all ages (and many in their 20's and 30's) - and they still picked us up and welcomed us as visitors. We've also worshipped at Cromer parish church, and were struck by the similarities between their situation and ours. They have two churches, one of which is the town centre church. It was great to see a large congregation in a growing church, with mixed ages, where they recognise the strengths of both traditional and more contemporary, and try to serve both their community and the many visitors who come through their building.

But visiting other churches has also made me appreciate what we have at St Mary's and St Peter's: both in terms of our congregational sizes, our buildings and resources, the options we can offer, our accessibility to new people and of course the profound prayerfulness, faithfulness and commitment of so many of our people.

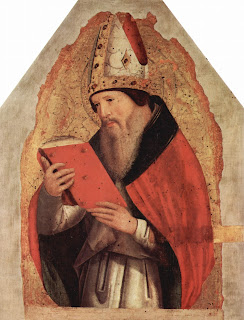

It is a privilege to have had time to read and think - and I am immensely grateful to the bishops and diocese, and our staff team and people for letting me have this time out. I've moved on from St Maximus the Confessor (580-662), and am discovering St Augustine (354-430). Augustine is one of those authors who I should have become more familiar with at theological college, and I've always felt both the need and the desire to read more from him. Although he is writing at a very different time, and fighting battles that are alien to us, yet his thought has profoundly shaped the way that we read and understand the bible and Christian faith. In particular I am looking at his understanding of love.

For both Maximus and Augustine, love of God is fundamentally about desiring God, a directing of our will towards God, which then shapes everything that we are and do. Augustine particularly is driven by the understanding that we all desire and seek happiness and life, and that only in loving God can we find ultimate happiness and eternal life. Our problem is that we look for those things in other places. Augustine was particularly aware, because of his past, how people look to sexual encounters and human love to satisfy those deep desires - but they are so shallow compared to what God can give. But this exclusive love for God that we are called to have does not exclude a love for other people. As we begin to respond to the love of God for us, and love and desire him in return, so God pours his love into us, and we are enabled to love others. I've been particularly challenged by the idea that love of neighbour will seek the very very best for them, which is not necessarily that we will be happy here (in what he calls 'the city of the world'), but that they - together with us, in Jesus, - will find that ultimate happiness and joy in loving God. In other words, not to speak with other people about the love of God and Jesus, and not to offer them the opportunity to seek God, is the most profound denial of the command to love our neighbour.

Comments

Post a Comment